A very special event indeed, what a time to be on strike. As of writing this, I’m still making up some strike pay hours. Nonetheless, I was extremely fortunate to view totality at a relatively clear location some hours away from where I am normally situated.

I went equipped with:

- eclipse glasses

- sandwich materials and some chilled diet coke

- a sweater

- and a lot of patience

We managed to find a park with an available bench to have the pre-eclipse picnic, then started checking through the glasses periodically, trying to find when the first visible blip over the Sun would happen (I had forgotten the specific times, and didn’t feel like looking it up). Here are some photos I took during the progression (Fig. 1).

For the most part, I was taking images through my cellphone camera and the glasses. Some branches did get in the way to make it difficult, but it was a fun exercise.

I had a burst of inspiration halfway through the eclipse and pulled out the photometer on my cellphone, laying it flattish along the arm of the bench. It registered around 50k lux around the midway mark. I checked on this periodically, with the value falling off during cloud passage or shadowing (inference, at first I thought it was just the eclipse progressing quickly!). When totality neared, the radiance value plummeted to a few hundred, and dropped further to single digits.

A couple of days later, it occurred to me it might be interesting to plot those values and see what it might look like. On top of that, was there some way I could estimate the incoming flux based on first principles? How accurate were my readings from my phone in comparison to weather stations? Let’s say I didn’t get far, but here is what happened.

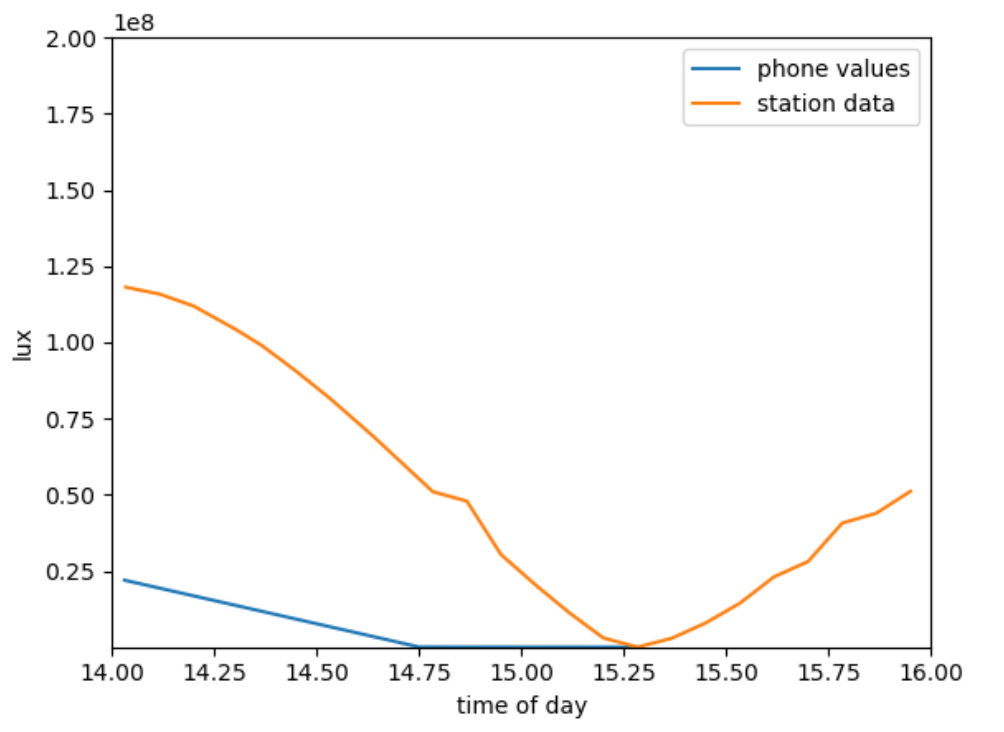

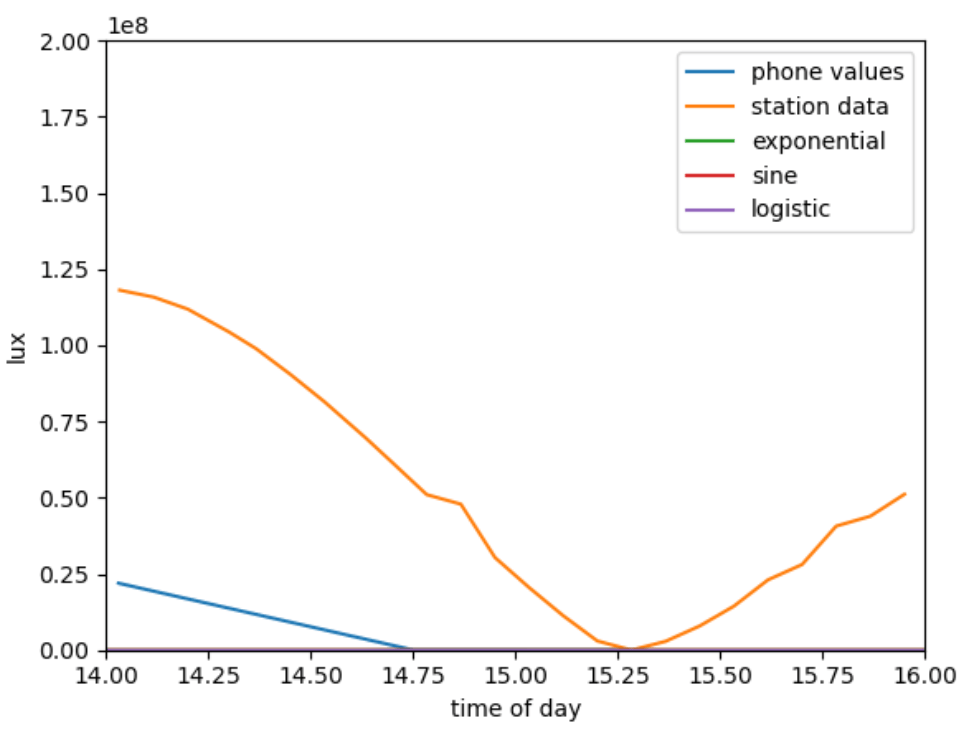

Here’s how I tried going about it. The first is getting the total incoming flux at the top of the atmosphere and how much is getting through the ground. I added some values from the typical incoming solar radiation and then some specific incidences at a nearby weather station. Clearly they were quite different from each other (Fig. 2). Nontheless, I also tried fitting the data points I took. I tried a few different curve fits and ended up with mildly ridiculous fits (Fig. 3). Intuitively, I had been expecting something like a sigmoid function to align well, though I received a suggestion for a gaussian fit to align with what we see from transits instead, which in retrospect, makes quite a bit of sense. However, this fell to the backburner and I didn’t get quite anywhere.

I don’t have much of a conclusion to this other than, a cellphone probably does not replace a pyrometer, and three data points does not make for a good fit.